For me, the key surprise is not that PRISM exists—it’s the lack of behavior change in response.

While the mass media claimed uproar and horror, 99.9% of people kept Googling, Facebooking and Skyping.

If you assume the worst-case scenario (i.e. total backdoor access for the US government), it would represent an affront to the basic fundamental rights of privacy. People have marched on the streets for less.

As we digitize more and more aspects of our lives and shift ourselves into the cloud, there is a very real prospect that everything we do can be monitored—yet few people alter their behavior. As PRISM has shown, the issue of digital privacy extends well beyond Facebook. The offense of privacy invasion is nothing compared to the exclusion caused by leaving the web.

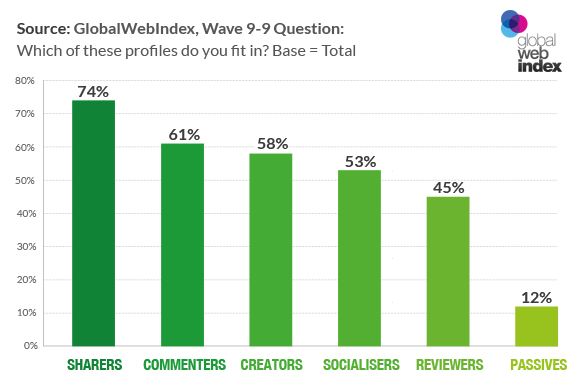

I believe this apathy is largely a reflection of 10 years of mass-market social media. GlobalWebIndex data demonstrates that over 88% of global internet users are now engaged in some form of social media. A mere 12% are passive consumers; 58% create social content and 74% share it in some form each month.

They are, in essence, erasing their personal privacy (see figure below).

As the tools to contribute and publish become ever simpler—and we move into frictionless sharing—I believe that total privacy will be a concept consigned to history. This is reflected in GWI data that has tracked sentiment towards the statement, “I am concerned about the internet eroding my personal privacy.” Regarding this question, 17% strongly agree—a figure that hasn’t budged for two years and shows that a strong number of users are impartial to privacy concerns.

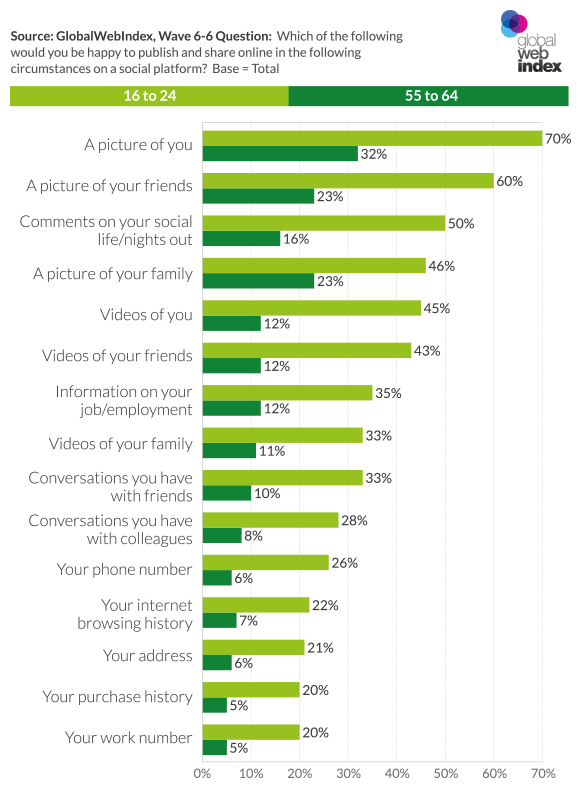

These trends are reflected in some already startling actions. In 2012, we ran a deep dive study into specific behaviors around the sharing of personal data. 18 months later, the fact that people are completely willing to share highly personal information still holds true.

Figure 2 shows how many users would be happy to publish on a social network using two opposed age groups, 16-24 and 55-64. While it was unsurprising that 70% of 16-24s are willing to publish photos, it is hugely surprising that 33% are happy to publish one-on-one conversations with friends and family, 26% a personal phone number and 20% their purchase history!

This is a clear divide with older groups, as only 32% of over 55s showed willingness to publish a personal photo. This shows the trend towards disappearing concepts of privacy, as digital natives display ease with personal data being published online.

I also believe there is a rational argument for the lack of consumer behaviour change in the case of PRISM. Today’s internet is so undoubtedly ingrained into the daily lives of the 2.4 billion who go online. Its perceived benefit is so great that we are often happy to tolerate its potential intrusion in exchange for the world’s information, people and knowledge.

What does this mean for brands?

Privacy concerns about cookies, tracking and behavioral targeting might seem trivial in comparison to PRISM. But this is not to say that the advertising industry shouldn’t be mindful of consumer privacy and protecting data, especially to target segments other than the youngest.

Instead, they should advocate the benefits privacy and take a more transparent and positive position than the U.S. Government. A great example of this, is Microsoft’s recent “Your Privacy is Our Priority” campaign, or the IAB Europe campaign to educate users on the benefits of behavioral targeting.

Should brands shout about the benefits of personalised advertising and content? Yes. But doing so is a two way street. As they become increasingly delivered by the internet infrastructure, both contextual and non-contextual tailored advertising will grow with sophistication and spread from online to TV and print.

They key is for brands to understand their unique demographics, what they are and are not likely to be comfortable sharing, and interact with them accordingly.

The increase in personalization is a double-edged sword: do it right, and you have the chance to build uniquely personal relationships based on trust—aka, to become a beloved yet elusive “meaningful brand”. Do it wrong, and you’re alienating more than a consumer—you’re offending a person’s sense of autonomy and privacy and de-valuing their priorities. Good luck getting them back.

Rather than being overall concerned with the “big brother” fears that consumers may have, the marketing sphere should embrace the chance to put privacy first and go the extra mile. It clearly isn’t crowded there.