Gaming has entered more and more marketers’ radars over the last 12 months, but misconceptions and stereotypes about the field are still plentiful.

There’s a lingering image of the young, male, and usually antisocial gamer. Think of the Big Bang Theory guys doing “Halo night”, or the kids in South Park playing World of Warcraft. Now unthink it.

Gaming has moved on from that stereotype, if it was ever accurate in the first place.

And with persistent multiplayer worlds easier to drop into than ever, gaming has become a kind of social media; a network of people all focused on doing something they enjoy and sharing their interests with others.

And just as with social media, it offers brands the chance to make meaningful activations with an engaged audience – assuming they get their execution right.

Just looking at players of specific devices or even franchises doesn’t quite give the whole picture.

For example, someone might play Minecraft on their own in survival mode, without ever touching the multiplayer.

As you would for any other demographic, it’s important to really delve into who your audience is and craft meaningful gamer segments, drawing particularly on their motivations to play.

Gaming is a “third place”.

It’s eye-opening to see just how central the social aspect is to gamers in 2021.

More gamers play to socialize with friends (26%) than to escape from reality (22%), or to immerse themselves in storylines (18%).

Here’s another way of taking that insight – players are more likely to see gaming as an enabler of their social networks, and not a retreat from them.

Fundamentally, it’s something that brings people together more than it splits them apart.

This has been cemented in recent years by the creation of bespoke “hangout spaces” in online video games, where there’s less emphasis on gameplay mechanics and more on relaxed social interaction. Fortnite’s Party Royale mode, Roblox’s Party Place, and GTA Online’s casino and resort are prime examples.

Coupled with other social-friendly franchises like Minecraft and Animal Crossing, these are sometimes referred to as “metaverses”, more akin to fully-fledged virtual worlds than games per se.

We can also understand them according to the sociological concept of the “third place”, spaces where people socialize outside of home and the workplace.

Without wanting to get too technical, the implications for brands are fairly simple – these new universes create opportunities for impactful campaigns.

Social gamers are committed and skew young.

So who exactly plays games to socialize?

You might expect social gamers to be more “casual”’ about gameplay, but it’s the opposite.

They skew more male, and are more likely to have a “hardcore” interest in gaming, saying they’re extremely or very interested in it.

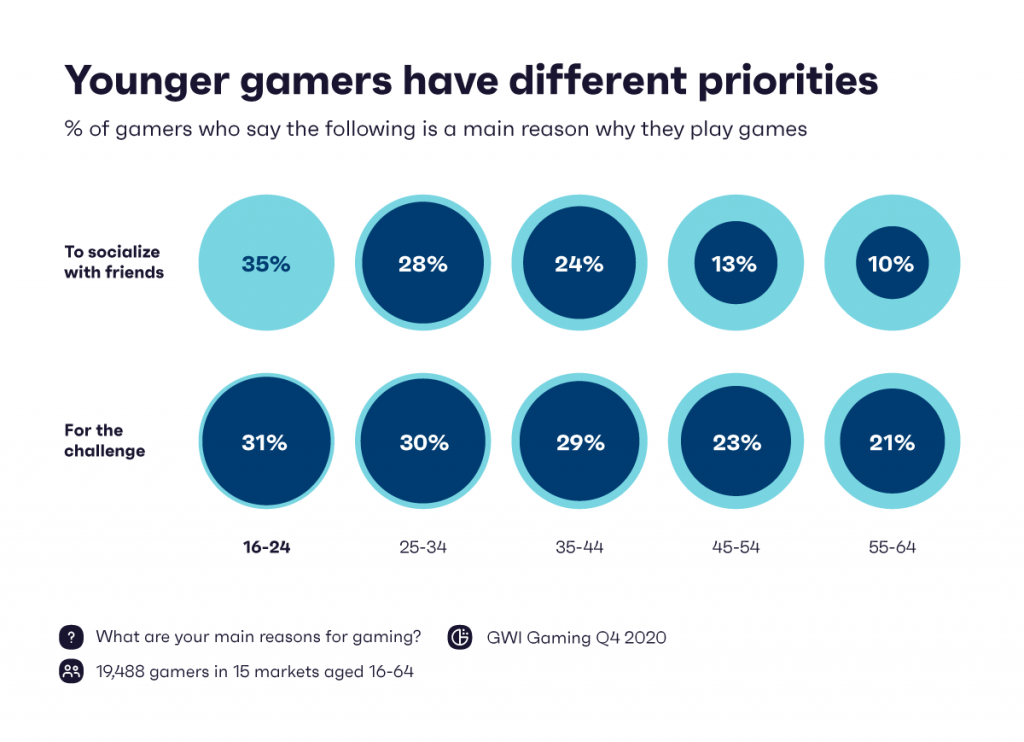

Playing to socialize is a huge thing among the youngest gamers, the 16-24s.

It’s sometimes missed just how much persistent multiplayer worlds have shaped their experience of gaming; younger players don’t really know the medium without it.

Older generations might still remember gaming as more of a single-player experience, and online servers were a more niche part of playing, but it’s now as easy to jump into a gaming world online as it is to log into Instagram.

In fact, 16-24s are unique in playing games to socialize more than for the challenge.

It’s the clearest sign of a generational shift in how they view the medium, and one that should overturn many long-held conceptions about it.

Community and competition go hand-in-hand.

Our Gaming dataset uses a recontact methodology, which allows us to profile different types of gamers against data points from our Core dataset, providing crucial detail about how they think and behave when they’re not gaming.

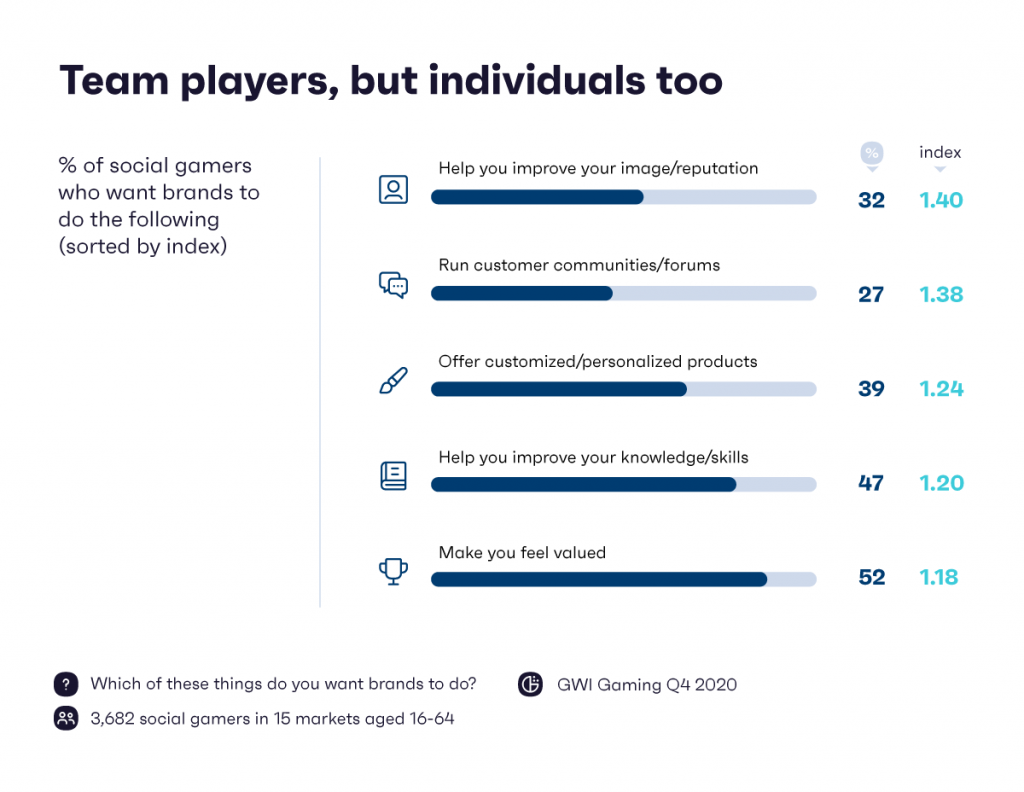

Broadly speaking, two themes emerge when analyzing social gamers which, at first glance, may seem contradictory.

They want to feel part of a community, but also to stand out. They’re team players, but also individualistic.

The best example of this is in their most favored brand actions.

More than the average, they’re into brands who improve their image/reputation, run customer communities and personalize products. A real mix of self- and group-directed actions.

Likewise, for their personal values, they’re more likely than average to say both standing out in a crowd and contributing to their community are important to them.

Putting these qualities into a gaming context, though, helps shed some light.

These social gamers want to feel part of the communities around the franchises they play, but also to stand out from other gamers within them.

Gamers will have avatars, characters, teams, vehicles, and just about anything that can be customised and curated to represent them.

Being a Fortnite player, for example, is a part of someone’s digital identity, but how they appear in the game adds another layer.

This is why cosmetics and skins in games like Fortnite can be so successful, as they’re effectively another layer of aesthetic competition between players underneath the traditional battle royale.

Nike’s work is a good example, as it brought the exclusive, limited-run culture of footwear “drops” into the game. It was delivered in a way that added value to the players (new gaming modes) but understood the competitive dynamics particular to gaming.

Even outside of competitive contexts, the principle of standing out while being part of a community still applies.

Animal Crossing players can feel bonded through their shared experience of playing the game, but the islands they look after are very much their own.

This is a crucial point that brands looking to get involved need to grasp.

It’s not just a case of understanding the culture around specific franchises and gaming worlds, but also tapping into these virtual projections of a player’s identity.

See you in the lobby.

Gaming is a kind of social media, but it’s not a one-size-fits-all.

You wouldn’t expect to copy/paste campaigns across any other social network, so brands have to do their due diligence on the community “feel” that’s unique to each gaming world.

More to the point, gaming is a social media where competition and socialising are finely intertwined.

While franchises are defined by their communities, individual gamers take pride in customizing their profiles in a way that gives them an edge and helps them stand out.